Executive Summary

This report explores and evaluates the potential for various algorithmic and machine learning approaches to extract key points of metadata from large collections of digitized images of manuscript letters. In particular, the problems of image classification/segmentation and image clustering/searching are explored in-depth, both by applying existing implementations of solutions for these problems as well as indicating alternate approaches suggested by the scientific literature for which no existing implementations are readily available.

This report is also available as a PDF.

Overview

The Alexander Stephens and William Wilberforce papers were identified as potential collections for experimenting with machine-extracted metadata from manuscript letters. Some potential candidates identified for extraction were:

- signature

- date

- location

All of these problems could be broken down into multiple common steps. These are:

- classification/segmentation: this is the problem of identifying the region in any whole image which can be classified as one of the pieces of interest (signature, date, or location)

- clustering/searching: this is the problem of taking the regions extracted by classification/segmentation and grouping together “similar” items, or searching across the whole collection for all occurrences of an extracted region

So, for example, if we were able to automatically extract every signature from every image, and accurately cluster together all images of the same signature, we could potentially cluster entire letters on that basis (and the identification of the person behind any signature cluster would give us writer identification for the entire associated cluster of letters).

A few different approaches could be taken for document image processing as well:

- a deep learning based approach, where a network is trained on a variety of inputs for a given problem

- a “traditional” computer vision approach, where various hand-coded image features are used to try to solve a specific problem

So, for example, to identify the signatures in the images, a deep learning based approach might take hundreds or thousands of images which have been manually labelled with the region of the image containing a signature (and then after training, be scaled up to extract signatures from many thousands of other images it has never seen before), where a “traditional” computer vision approach might involve designing an algorithm which says something like “after segmenting lines and clustering connected components, identify the signature as the bottom-right connected component”.

In order of decreasing time/resource requirements:

- developing a custom deep learning or “traditional” computer vision implementation from scratch

- training an existing deep learning implementation on a custom dataset/problem, or slightly modifying an existing “traditional” implementation

- using an existing implementation (and pre-trained network)

There are a few difficulties with applying existing approaches to handwritten documents. For both deep learning and traditional approaches, many papers are published with promising results for various parts of the problems we face, with no implementations published alongside them, putting them in the most time-intensive category. A second issue is that many deep learning approaches are currently focused on photographs and images, so a majority of the existing open approaches and pre-trained networks are geared towards problems in that domain and may not perform as well for handwritten documents without customization.

Classification/Segmentation

Generating Training Data

Out of the 11,348 total images in the input data (the Stephens and Wilberforce papers combined), 200 images were selected at random to use for manual segmentation and initial training set creation. These images were then manually tagged for “signature”, “date”, and “location” using the Microsoft Visual Object Tagging Tool. In the tagging process, a number of issues arose while attempting to tag the data:

- multiple signatures: sometimes a letter would have multiple distinct signatures, or be signed by one person on behalf of multiple people

- data disparity: “letters” vs. “envelopes” are very disparate in the placement and character of each of the tagged fields. Due to the anticipated poor outcome of trying to train segmentation for both classes of image on such a small sample size, I decided to segment only the “letters”. Likely a better approach would be to pick out just “letters” for initial tagging/training. There’s also some potential concern that the relative sizes of the two combined collections will bias the classifier toward performing better on the collection with more data - the Stephens papers made up 8,648 images of the total collection while the Wilberforce papers contained only 2,700 images

Because of the data disparity issue and the need to split training data into train/test sets for training, out of the original 200 randomly-selected images only 100 were used as training inputs with labels. Increasing this training dataset would likely increase the accuracy of results.

Generating a Trained Classifier

Because I’d successfully experimented with using it for other classification/segmentation tasks in the past, I originally wanted to try using dhSegment for the segmentation task. This is a deep-learning-approach-based tool developed out of the EPFL DHLAB which uses a pre-initialized residual network (ResNet-50) to reduce the training requirements and improve performance.

However, the input expected by dhSegment didn’t match any of the export formats supported by VoTT, and I would have had to write a custom program to transform the manually labeled data into the expected format. Fortunately, VoTT supports exporting to a variety of formats directly supported by other state-of-the-art image classifiers.

Ultimately, I decided to use “You Only Look Once” (a.k.a. YOLO), because it supports whole-image classification (rather than neighborhood classification, which breaks each input image into subregions before attempting classification–the relative position of objects to the whole image is important for our classification problem) and uses a residual network training approach similar to dhSegment to reduce the training overhead.

The general recommendation for training YOLO is that you’ll begin to see good results at (2,000 * number of classes) training iterations. Since we’re training on 3 classes (signature, date, location), we’d need at least 6,000 iterations. Starting the training on my iMac with a GTX 780M GPU, I was able to train around 1,000 iterations in 24 hours - so a full initial training would take around a week. After moving the training to a cloud computing instance with two GTX 1080 GPUs, I was able to complete another 16,000 training iterations in around 6 hours.

Using the Trained Classifier

Once I had enough training iterations that I was comfortable I could start to see some results, I halted the training process (which can be run indefinitely, though this will result in “overfitting” the training data - i.e. the classifier will perform perfectly on images it has already seen, but poorly on images it has never seen). After spot-checking the classifier on some images, I was able to run the classifier across the entire dataset locally (with a GTX 780M) in around 30 minutes. For each image, this gave me bounding boxes and associated confidence levels for all three classes of detected objects (see Figures 1 & 2).

Figure 1 - An example of correctly classified features in context

Figure 2 - An example of a date incorrectly classified as an additional signature due to positioning

I then wrote a small script to take these results and output the cropped region corresponding to the highest confidence level for each class of object for each image. So every image with any detected object above a 0% confidence level would have the highest-confidence object output, which could then be used for clustering. Since not every image actually has all three classes of object, this poses another challenge, which is determining the best place to set the confidence threshold - in some cases the top-rated object for a given class may have a confidence of less than 1% (but greater than 0%), for example. Sometimes these can be valid objects in the given class, but at e.g. the <1% confidence range many of these objects will be incorrect.

For each of the following downstream classification and searching tasks, I didn’t apply any such confidence thresholding, aside from the initial >0% confidence threshold. For a production system with a more robustly trained classifier, stricter thresholding may be desirable (see Figures 3-5).

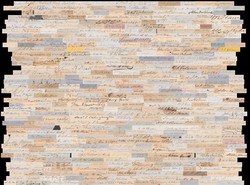

Figure 3 - A sample of signatures extracted by the trained classifier

Figure 4 - A sample of locations extracted by the trained classifier

Figure 5 - A sample of dates extracted by the trained classifier

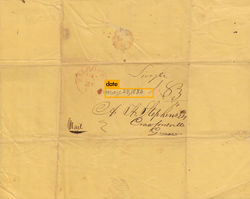

One surprising result was that despite not training on envelope data, and the relatively small training set, the classifier was still able to correctly classify fields from envelopes correctly in some instances (Figure 6).

Figure 6 - An example of the classifier correctly detecting a date on an envelope

Clustering/Searching

Clustering

A few different existing implementations were experimented with for clustering the images:

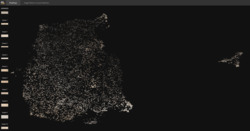

- PixPlot, from the Yale DH Lab, computes feature vectors using a model trained on ImageNet called “Inception”. This is a visual recognition model trained for classifying entire images from a large photographic image database (over 14 million images) into one of 1,000 classes (“like ‘Zebra’, ‘Dalmation’, and ‘Dishwasher’”) (see Figures 7 & 8 for example output).

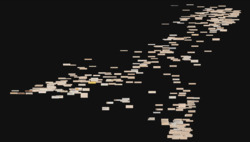

imagecluster, which uses the VGG16 model (similar to Inception and also trained for the ImageNet task), with hierarchical clustering of the resulting features (see Figures 9 & 10 for example output).

For both of these clustering approaches, I experimented with clustering both the entire uncropped image sets, as well as the dataset of auto-extracted cropped signatures from the classification process described above. In general, likely due to the image/photographic focus of the trained model used for computing feature vectors, these clustering processes were able to do well at clustering e.g. handwritten vs. typed (see Figures 7 & 8), or shared graphical features across letters (see Figure 9). A surprising instance of the latter was the imagecluster clustering process using shared rips and folds in the images to cluster together a multi-page letter which had consistent rips and folds across its pages (see Figure 10). While in this case the individual pages were still catalogued together, the clustering process did not have access to this metadata, and still managed to cluster the pages together based on the visual features alone - which may be a promising approach for other materials with poorer cataloguing. In many cases, these sorts of visual clustering algorithms could be used to preprocess the dataset or assist manual application of broad metadata fields, e.g. by classifying typewritten or photographed materials or excluding them from further handwriting processing.

Figure 7 - PixPlot clustering of extracted signatures

Figure 8 - Zoomed view of the “typeset” outlier cluster of extracted signatures in PixPlot

Figure 9 - Checks clustered together by imagecluster

Figure 10 - Pages of a letter clustered together by imagecluster on the basis of consistent rips

Another option for clustering I came across would be to directly use intermediate feature vectors from our own trained classifier to try to do the clustering. Because these are the feature vectors our own classifier is using internally to distinguish among signature, date, location, and other text, the features are likely to correspond strongly to features that we’d be interested in for clustering. Unfortunately, while this may this may yield better results, it would also require a fair amount of custom code.

Searching

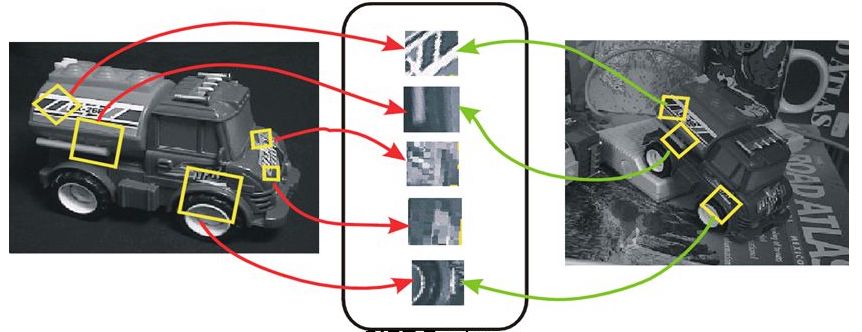

Another approach would be to use a “reverse image search” on cropped regions with a database of all the images. This would seem to have potential to work well with unique signatures - finding all instances of a given signature in the image database. Reverse image search can be implemented in a number of ways, depending on what you want to find for a given query image (for example, a reverse image search algorithm focused on finding people in an image set might use face detection/recognition, which would be a poor fit for many other tasks). For our task, an image search algorithm based on “traditional” geometric computer vision features would seem to be a good fit. That is, for a given input image, we want to compute feature descriptors based on areas of contrast in the image, where the feature descriptors are robust to scale, rotation, and affine transformation (see Figure 11), so that we can match query images which are similar but not exact (e.g. a signature, and a slightly larger/rotated version of the same signature).

Figure 11 - An example of “traditional” geometric Scale-Invariant Feature Transform (SIFT) feature descriptors being matched across two images

A few different existing reverse image search implementations were experimented with:

- Pastec Image Search: I had used this reverse image search engine with success previously for matching large collections of images from the Rijksmueum and New York Public Library. Since it uses traditional geometric features, I thought it might potentially work well for matching our extracted signatures. Unfortunately, while in many cases it was able to match a query signature to itself, the few instances where it was able to turn up multiple matches for a query image were usually erroneous (i.e. an unrelated extracted signature, which the engine had decided was “similar” based on its internal metric).

- “Match” reverse image search: another open-source reverse image search engine which used traditional geometric features for matching. Results for the extracted signature matching task were, unfortunately, similar to Pastec as described above (extracted signatures were easily able to be matched to themselves, but the few instances of multiple matches were usually erroneous).

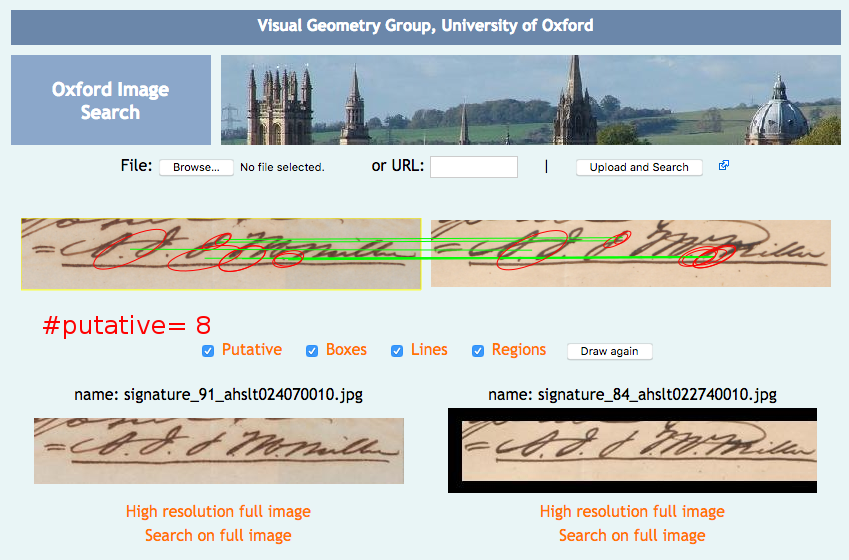

- VGG Image Search Engine (VISE): the indexing process for this engine is extremely slow for large datasets, and whenever I attempted to index the full dataset of cropped signatures the program would eventually crash during indexing. By restricting the indexing to only signatures with a confidence >=50% (1,890 images), I was eventually able to successfully complete indexing and test some searches. While searching was very fast, I was only able to obtain one correct signature match in my experiments (Figure 12). After further investigation, a major upgrade of this search engine is currently in beta, which aims to provide faster indexing, larger dataset handling, and a REST API (which would make exhaustive/systematic investigation of search results much easier). While the “beta” status of this update made it too time-consuming to trial for this experiment, it may be something worth revisiting in the future.

- Lucene Image Retrieval (LIRE): implements a variety of image indexing and retrieval methods, backed by Lucene. Out of all the reverse image search engines tried, this seemed to have the best results. After indexing the full set of extracted signatures, I was in some cases able to find other instances of the same query signature with different methods (Figure 13). A more methodical approach to determining the best methods (and combining the results, as in some cases one method will find a signature not found by another method and vice-versa) may yield more consistent and promising results.

Figure 12 - The successful match found in VISE, which allows more detailed examination of matches

Figure 13 - An example of a LIRE query retrieving multiple matching signatures (as well as some incorrect matches). The query image is exactly matched in the top-left

There were also some other open-source reverse image search implmentations which I attempted to use but was unable to due to various difficulties:

- “Deep Video Analytics”: advertises itself as providing a variety of options for indexing and searching video and images. Unfortunately, while I was able to get it running superficially, I encountered an error whenever I attempted to index images.

- Kitware KWIVER: required complicated build dependencies, which resulted in errors when trying to compile.

Other Approaches & Techniques

Other techniques such as HTR (Handwritten Text Recognition, essentially OCR for handwriting) are emerging, however, these generally must be trained per-hand and currently have relatively steep training requirements. The HTR platform Transkribus, for example, requires 15,000 words of transcribed handwritten text to start training a usable model.

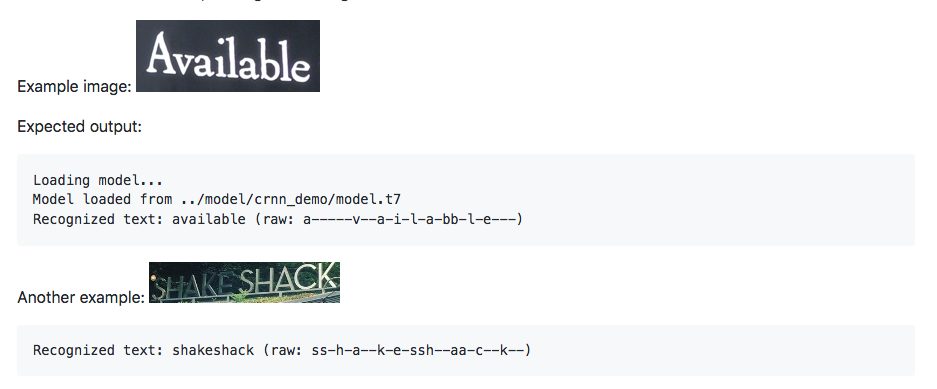

A related approach (which some HTR approaches may rely on) which may have some promise would be to train a Convolutional Recurrent Neural Network (CRNN) for text recognition only on extracted dates or locations (see Figure 14). A potential advantage of this approach is that it can also be trained or used in a “lexicon-based” mode, so dates for example could be restricted to a date lexicon consisting only of the possible date strings that might occur in a collection in order to improve accuracy.

Figure 14 - An example of a CRNN performing difficult text recognition tasks

Another technique I initially thought I could use to process the data is “Word-Spotting”. This is a technique which enables searching for words in sets of images by using image feature matching; a query against the image database is run using a feature set generated either by a query image (i.e. a cropped date or signature) or by generating a synthetic feature set from a text string (i.e. “Aug 4 1887” is transformed into the approximate expected image features, sometimes by first generating a synthetic image in the appropriate script and hand). My expectation was this could work well for signature matching by image query - other fields may have more variance in hand, but individual signatures would likely be relatively regular in terms of their image features, so that by selecting an individual signature in one letter you could query the entire image set for all other appearances of that signature. The difficulty with this approach was simply that despite the large number of papers describing various word-spotting approaches, I wasn’t able to find much in the way of existing open-source implementations. This also reduces word-spotting to essentially the reverse image search approach described above, just with features tuned to handwriting.

Conclusions

An interesting result from all these experiments is that my intuition going into this was that the clustering/searching would be the “easy” part of the problem (since it relied on more traditional computer vision methods), while the classification/segmentation would be the “hard” part (since it relied on more cutting-edge experimental deep learning methods, and could require a large amount of training data). The results instead seem to bear out the opposite: while increasing the training set size and customizing/improving the training configuration could likely go a long way toward improving accuracy/confidence, the classification/segmentation approach used yielded much more promising initial results. These could be used to further and better define the clustering/searching problem, or could even be used to reduce manual labor or increase discovery absent this problem being solved (e.g. displaying auto-extracted signature, date, and location images alongside a record for viewing or transcription).

Next Steps

As discussed in the overview, the potential solutions to these problems lie along a spectrum of difficulties: while it’s possible to assemble existing solutions and obtain some easy results, much better results may be available by investing in the development of customized solutions for the specific problems posed by the data. In the case of handwritten letters, while there’s a relatively large amount of published research for image processing approaches to various parts of these problems, there’s far less in the way of published implementations. This may point to a need for development in this area. Of course, this need must be balanced with the potential reward, but the potential for this extends far beyond just the letters chosen for this pilot project: one can easily imagine a platform for processing handwritten letters more generally which would be of use for a vast array of collections, both those already digitized but also those deemed too daunting for digitization with the present state of tools and capacities for processing.