A little over a year ago, while photographing various objects held in museums in Rome, I came across the following strange artifact in the Epigraphic Museum of the Baths of Diocletian:

The museum placard reads thus: 1

Libello “basilidiano”

Libello formato da sette pagine racchiuse da un copertina con la testa di una donna velata e di un uomo barbato. Nelle pagine opistigrafe, sono incise coppie di figure, umane e animali in probabile successione, e un testo ricco di segni magici (charaktères), che non sembra avere senso compiuto.

Provenienza ignota, già nel Museo Kircheriano - IV-V sec. d.C.?

A little book

A book formed of seven pages enclosed by a cover with a veiled woman’s head and a bearded man. On the inside pages, engraved on both sides, a couple of human and animal figures are depicted probably at a latter date. Even the date [sic]1, rich of magic signs (charaktères), does not seem to make sense.

Origin unknown, already in the Kircherian museum - IV-V century AD?

The object was intriguing to me, as a metal codex is a relatively novel form, and I’d heard nothing of this particular object during the Jordan Lead Codices controversy (what ever came of that?). Mormons also have an especially strong interest in trying to prove the existence of a tradition of metal codices, and seem from my investigations to have no idea of the existence of this one. Surprisingly, this object is also nowhere to be found in the 2004 museum catalog.

The provenance on the placard is also mysterious: “Origin unknown, already in the Kircherian museum”. This seemed my best foothold for finding any further information about it. First off, what’s the Kircherian museum? According to the Italian Wikipedia page:

Il Museo kircheriano fu una raccolta pubblica di antichità e curiosità (Wunderkammer), fondata nel 1651 dal padre gesuita Athanasius Kircher nel Collegio Romano.

The Kircher Museum was a public collection of antiquities and curiosities (Wunderkammer), founded in 1651 by the Jesuit father Athanasius Kircher in the Roman College.

Apparently over the ages the collection was dissolved and reabsorbed into various other collections. The rough timeline seems to be that this object “remained”2 in the Museo Kircheriano at the Collegio Romano3 from at least 1837 until its ultimate dissolution in 1913,4 ending up in its present location. Where, when, how, and even in what form it came into the Kircherian is debatable.

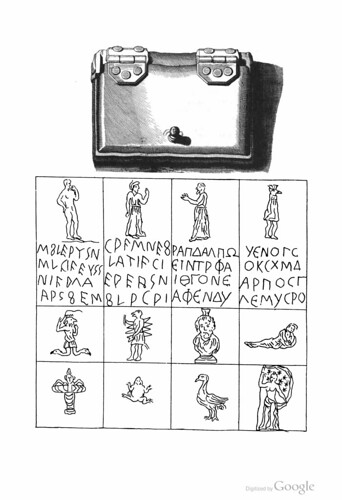

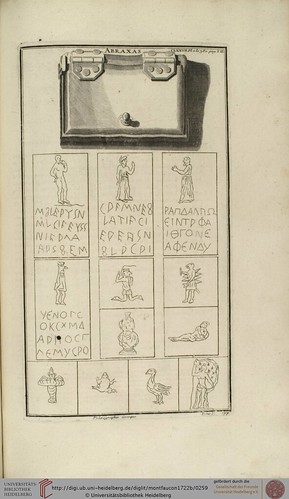

Chasing down publications about this object has proven difficult and confusing, as there are (or were), potentially three different but superficially similar Basilidian metal codices which seem to have appeared in Rome around the same time:

- the one currently preserved in the museum (7 plates, 2 figures and 5 lines on each side)

- a different one published by Phillippo Bonanni, mentioned in his 1709 catalog of the museum, but “vanished” or replaced with the present one sometime before 18372 (7 plates, 2 figures and 4 lines on each side?)

- a still different one purchased in Rome by Bernard de Montfaucon in 16995 then donated to Cardinal de Bouillon, which also vanished sometime before 18286 (6 plates, 1 figure on each side and 4 lines on the first four)

Out of all the publications relating to these objects, Bonanni is the only one who seems to give any sort of potential provenance information (“Fuit hic plumbeus liber repertus in antiquo Sarcophago, in quo cineres demortui fuerant inclusi. — In this case the leaden book was found in an ancient sarcophagus, in which the ashes of the deceased had been shut up.”).

What I propose to set forth in this post is a chronological bibliography of everything I’ve found relating to these three metal codices, providing transcriptions of these texts and a rough pass at English translation where applicable.7 My hope is that collecting this material in one place will enable further scholarship in a neglected and apparently obscure area. Many of the sources I came across in my research note casually that Bonanni (and Contucci) considerably expanded the collection of antiquities in the Kircherian museum, and the provenance of many of these objects (now dispersed and displayed in other museums) is presumably similarly difficult to trace. Thus it seems to me that a useful project for an ambitious researcher interested in these matters would be to try to locate correspondence, archives, or other unedited manuscripts related to these curators and edit them on the model of Alberto Bartola’s Alle Origini del Museo del Collegio Romano and Nathalie Lallemand-Buyssens’ Les acquisitions d’Athanasius Kircher au musée du Collège Romain à la lumière de documents inédit. The two sources mined by these articles are the Apostolica Pontificia Universita Gregoriana, Rome (APUG) and Archivum Romanum Societatis Iesu (ARSI), respectively, and given the size of these archives there still may be relevant material yet to be discovered.

Lallemand-Buyssens also notes the difficulty of figuring out when a particular object entered or left the museum as constituted at any particular point in time, and that many of the catalogs are not (and do not claim to be) comprehensive. However, given Kircher’s interest in and voluminous writing on other gnostic artifacts in the museum, and the fact that this artifact goes unmentioned by him in any work that I can find (perhaps it was in his lost Etruscan Journey?),8 as well as its absence from the items mentioned by Bonanni as remaining in the museum as it stood in 1698 (as described in his 1716 Notizie circa la Galleria del Collegio Romano, an edition of which can be found in Appendix III of Bartola),9 I think it is safe to assume that at least the artifact published by Bonanni in 1709 was acquired by Bonanni. That artifact’s replacement with the current one may be another story entirely, and one which has apparently confounded many.

Table of Contents

- Preface

- Chronological Bibliography

- Bibliography (Kircher & the Kircherian)

- Bibliography (Bonanni)

- Footnotes

Preface

The following mere chronological presentation of the sources discussing these objects will probably give the reader a good view of some of the confusions and contradictions that have arisen in trying to research this topic. For one, half of the sources seem bent on misreading and misinterpreting that which came before them; for example King heaps scorn on Matter for confusing the present Kircherian artifact with Montfaucon’s, when Matter appears to do no such thing and in fact goes to great pains to note the differences between both of them and Bonanni’s, a distinction which King misses. For another, many of the sources are primarily preoccuppied with reciting every classical attestation of writing on lead. Maybe I have the benefit of the distance of time and the later archaeological finds and the scholarship which comes with them, but it seems to me that the oft-cited passage of Tacitus10 is discussing lead curse tablets, which appear to me a very different thing from what we have here.

One interesting facet to all this is that the descriptions given by Brunati, Ruggiero, Reisch, and the museum placard of the cover having a “bearded man” and a veiled woman match in description and arrangement the side of the cover we can see in Bonanni’s illustration (unfortunately, I did not get a good photograph of this side of the cover as it stands in the current museum, though what is visible of it matches;11 oddly, Matter says he did not know of any cover that went with his sheets).12 Additionally, Brunati makes the distinction of calling the pages “aeneis” (copper) rather than “plumbeo” (lead), which I initially thought was a mistake, but upon further examination may have been a more considered judgement. Is it possible that what has occurred here is that Bonanni’s “original”, at some point between 1709 and 1837,13 was disbound in order to have the pages sold off and replaced with forgeries while the cover was retained? Are the pages that we have modern forgeries modeled after two lost, potentially genuine, artifacts?

Chronological Bibliography

-

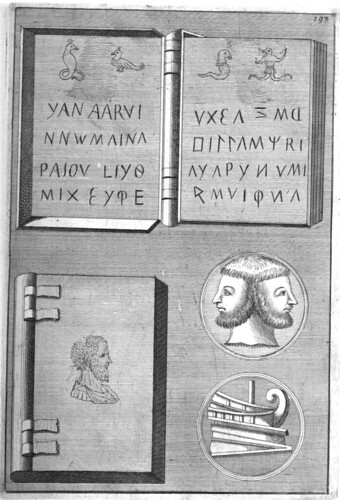

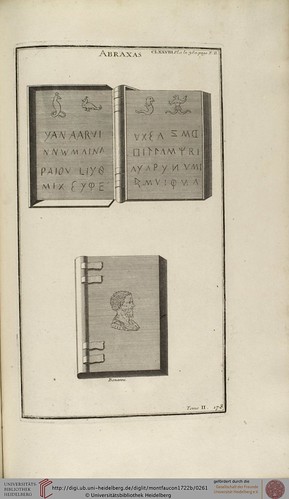

Bernard de Montfaucon, Palaeographia Graeca. Paris, 1708. p. 181.

Dum Romae agerem, incidi in librum plumbeum, insculptum literis & figuris Basilidianorum: emtumque obtuli Serenissimo Principi Cardinali de Boüillon; ita tamen ut depicta omnia penes me remanerent. Est is libellus longitudine quatuor circiter pollicum; latitudine duorum & dimidii, ut infra delineatur: operculis vero duobus plumbeis totus compingitur, sex folia item plumbea sunt, ab utraque facie incisa literis aut figuris: duae partes operculi assumento plumbeo, clavis item plumbeis asserto & firmato, junguntur. Virgula plumbea foliis a tergo, per annulum plumbeum ipsis haerentem, inserta, ipsa folia retinet ne dimoveantur. Denique omnia plumbum. In singulis paginis Basilidianorum figurae comparent. In quatuor primis tantum, verba quaedam sub figuris posita incisa sunt. Prima & secunda pagella, Hetruscis literis exaratur; tertia & quarta Graecis; ex utrisque tamen tam Hetruscis, quam Graecis, tantumdem notitiae expisceris, adeo sunt obscura omnia & tenebris oppleta. Hactenus quod ad literas: quod ad figurae vero haec carptim dicamus. In prima pagina, homo nudus stat, digitos ori admovens, qualem depingunt Harpocratem: nimirum illi fabulosa & prophana omnia sectabantur. In secunda, homo veste talari indutus, manu caelum commonstrat, quo mysterio, divinet qui possit. In tertia, Basilidianus quispiam junctis manibus, nudo capite precans effingitur. In quarta pagina, figura humano corpore, capite volucris coronato: quales non paucae in lapillis habentur. In quinta, Abraxas humano corpore, galli gallinacei capite, dextera flagellum tenens, sinistram ori admovens, tibiis in serpentis caput desinentibus: de quo pluribus supra. In sexta, homo stans, capite volucris, radiato corpore, baculum manu dextera tenens: quae figura non insolita est in lapillis & gemmis. In septima, caput Jobis Serapidis, qui in Basilidianorum lapillis frequentissime repraesentatur, interdum solus, nonnumquam cum aliis figuris. In octava, mulier decumbens, quam figuram numquam alias inter Basilidianorum symbola vidi. In nona, insectum animal, ex variis insectis compositum: qualia multa comparent in gemmis Abraxaeis. In decima, rana, quod animal mirum quantum celebretur apud Basilidianos; ita ut homines ritu venerantium in conspectu ranae depingantur. In undecima, avis quaedam, anseri non absimilis. In duodecima, mulier, velo stellis consperso caput obvelans, quae est figura noctis: eam quidem in Basilidianorum gemmis & symbolis numquam vidimus; sed constat certissimumque est, hoc schemate noctem significari, ut supra Libro primo, capite primo videas. Hinc vero subit in mentem, hunc duodenum numerum aliquid significare, & conjecturam meam, amicis probatam, Lectori benevolo aperire non pigebit. Opinor itaque hisce duodecim schematibus, duodecim diei horas indicari. Ad primam quippe diei horam homo nudus repraesentatur, quia tunc e lecto surgitur. Ad horam sextam, sive meridiem, homo gradiens radiatus volucris capite depingitur: quod symbolum est solis medium cursum tenentis. Ad duodecimam, mulier stellato velo caput obnubens, quod apertissimum est, uti jam diximus, noctis signum. Ex hisce tribus clarum videtur hic horas indicari: nam quorsum haec spectare possint? Jam vero horas singulas, quantum quidem licebit, prosequamur. Hora itaque prima Basilidianus e lecto surgit nudus: siquidem haec Basilidianos & Gnosticos spectare conspicuum est. Hora secunda, veste talari indutus, operto capite, caelum manu ostendere; aut aliud quidpiam ignotum significare videtur. Hora tertia, ut moris erat Christianis, nudo capite, junctis manibus precatur. Ad horam vero quartam, quo spectet homo ille capite & rostro volucris, coronatus, ne quidem conjectare valeam, nec quid ad quintam horam sibi velit homo galli gallinacei capite, tibiis in serpentis caput desinentibus: qua in re malo ignorantiam prositeri meam, quam levia & incerta proponere. Ad horam sectam, homo gradiens radiatus, volucris capite, baculum manu tenens, solem medium cursum tenentem adumbrat. Hora septima, Jupiter Serapis, qui teste Hadriano in epistola sua a Christianis colebatur, depingitur: quia erat ἑπταγρἀμματος θεός, Septem literarum deus: nam totidem sunt in nomine Σεραπις, vel Σαραπις, utroque enim modo legitur. Hinc Hesychius, [untranscribed Greek] & vetus Epigramma: [untranscribed Greek] Hoc est: Septem me pronuntiatae Deum magnum incorruptum laudant Literae, omnium indefessum parentem. Posset item fortasse dici, Serapidem hora septima, quae est prandii tempus, apponi, quia est deus frugum colendarum, quibus colligendis modium capite gestat. Ad horam octavam, mulier decumbens pomeridianum forte somnum adumbrat. Ad nonam vero, quid sibi velit insectum illud ignoramus. Ad decimam, inclinante jam sole, rana depingitur, quia fortasse tum maxime coaxare & strepitus edere incipit. In undecima anser cadente sole ad quietem & cubile pacate concedit. In duodecima nox advenit, quae per mulierem stellato amictu obvelatam certissime adumbratur. Hic porro notandum est, Basilidianos, ut ad solis cursum, quem in religione ponebant, repraesentandum, 365. virtutes comminiscebantur: quarum singulas & nomine, & schemate, ut creditur, proprio designabant; sic ad diurnum solis cursum, virtutes, & figuras duodenas, pro singulis horis designandis, constituisse vero simile est. Quod etiam conjecturam confirmat nostram: quam tamen eruditorum arbitrio permittimus.

While I was working in Rome, I came across a book of lead, engraved with Basilidian letters and figures: which I have offered the most excellent Prince Cardinal de Bouillon; all depicted in such a way that should remain in my memory. The book is about four inches in length; the size of two & a half [inches] long, as will be outlined: two lids of lead completely linked, six leaves of lead within, either face incised with letters or figures: two parts of the lid are patched with lead, a leaden key protecting & foritifying, are joined. A lead rod behind the leaves, or rings of lead themselves clinging, inserted, the same leaves retainining their positions. In short, all is lead. In the individual pages Basilidian figures appear. In the first four only, some kind of words have been placed under the figure incised there. In the first and second pages, Etruscan letters are written; in the third and fourth Greek; From both, however, the Etruscans, and the Greeks, I find much knowledge, they are so filled with all matter of obscure & dark things. So much for the letters: let us discuss the different figures. In the first page, a man is standing naked, fingers in his mouth and blowing, a sort of depiction of Harpocrates: evidently to him fabulous & profane all following. In the second, a man clothed with a garment down to the foot, the hand pointing to heaven, what mystery, what can be guessed. In the third, a Basilidian with hands joined in prayer, praying in a bareheaded fashion. In the fourth page, the figure of a human body, crowned with the head of a bird: the sort which is depicted in no small quantity of stones. In the fifth, Abraxas in human form, with rooster head, his right hand holding a whip, left hand held up to his mouth, with the legs of a serpent breaking off from his head: as in the majority of cases above. In the sixth, a man is standing, with the head of the bird, radiant body, holding a staff in his right hand: this figure is not unusual in stones & gems. In the seventh, the head of Jobis Serapis, who is frequently represented in Basilidian stones, sometimes alone, sometimes with other figures. In the eighth, a woman reclining, a figure never before seen among Basilidian symbols. In the ninth, an insect creature, made out of a variety of insects: many comparable sorts are in Abraxian gems. In the tenth, a frog, an animal that is celebrated by Basilidians as having many remarkable effects; such that men worship with veneration the depictions of frogs. In the eleventh, a certain bird, not unlike a goose. In the twelfth, a woman, a veil sprinkled with stars covering her head, which is the figure of the night: indeed in Basilidian gems & symbols she is never seen; but it is clear and certain, this figure signifies the night, as seen above in the first book and chapter. From this truly it stands to reason, what these 12 numbered signs signify, & my conjecture, I demonstrate fondly, do not be troubled dear reader. I think that these 12 figures signify the 12 hours of the day. For the first hour a naked man is portrayed, because that is when one rises from bed. At the sixth hour, or noon, a man with radiant body and the head of a bird is depicted: this is the symbol of the sun in the middle of its course. In the twelfth, a woman covering her head with a veil of stars, which is clearly, as we have already said, the sign of the night.Out of this third part we see here clearly the hours indicated: what else can these possibly be? Truly, pass all the hours one at a time, how many are permitted, I describe in detail. So for the first hour a Basilidian rises nude from bed: supposing this is Basilidian & Gnoctic, it can clearly be seen. For the second hour, clothed with a garment down to the foot, having his head covered, hand pointing to heaven; this seems to signify the unknown. For the third hour, according to Christian custom, bare head, hands joined in prayer. At the fourth hour, in which we see the man with the head & beak of a bird, crowned, I cannot even guess at, nor what it means to take up in the fifth hour a man with the head of a rooster and the legs of a serpent: in this matter my poor ignorance wears away, what levity & uncertainty I display. At the sixth hour, the radiant man, head of a bird, staff in hand, representing the sun in the middle of its course. At the seventh hour, Jupiter Serapis, who is witnessed by Hadrian in his letter on Christian worship, is depicted: because it was ἑπταγρἀμματος θεός, Seven-lettered god: for there are as many in the name Σεραπις, or Σαραπις, it is read both ways. Hence Hesychius: [untranscribed Greek]: & the ancient epitaph: [untranscribed Greek] This is: Seven I proclaim for the praise of the great and pure God Letters, the all-untiring offering. It would be possible to be said, too, perhaps, at the seventh hour, which is dinner time, Serapis is set, because it is the god of crops and growth, which carries the basket for harvesting on its head. At the eighth hour, a woman is shown reclining in the afternoon perhaps asleep. For the ninth hour, however, what is meant by an insect we do not know. The tenth, the sun was already going down, a frog is depicted, perhaps especially then it croaks & makes noise and begins to eat. In the eleventh hour, a goose typically peacefully departs to its nest. At the twelfth night comes in, which is certainly represented by the woman veiled with stars. At this point it should be noted further, Basilides, to get to the course of the sun, which he set down in religion, to represent 365. virtues he recounted: of which every thing and name, and a diagram, as is believed, one’s own mark; thus it belongs to the daily course of the sun, the virtues, and the twelve figures, for each of the designated hours, as has been established. In this too our conjecture is confirmed, which, however, awaits the judgment of the learned.

-

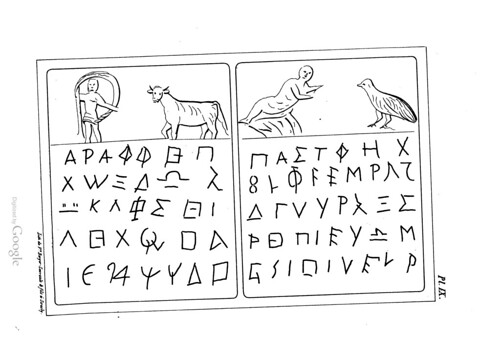

Philippo Bonanni, Musaeum Kircherianum sive Musaeum a P. Athanasio Kirchero in Collegio Romano Societatis Jesu. Rome: Typis Georgii Plachi, 1709. p. 180.

Thecam plumbeam expressimus in Tabula LX. in formam libri compactam, in qua septem laminae etiam plumbeae includuntur, inquarum singulis plures characteres incisi fuerunt verriculo, & quidem non unius idiomatis, sed variarum linguarum; sunt enim aliqui ex graeco Alphabeto selecti, aliqui verò ex haebraico, multi ex antiquo Ethruscorum, varii ex latino. Horum Characterum combinationes verba intelligibilia efformant, quae nec Graecus, nec haebraici, neque latini fermonis licet peritissimus intelligere nunquam potuit. Singulis etiam laminis adjecta sunt aliqua symbola, at ex nullo eorum deduci potest, quid Artifex mente conceperit, quod indicaret. Quamobrem in genere Talismanorum enumerandam esse judico, in quibus Antiquorum superstitio id exprimebat, quod erronea mente conceperat, putabat que optimum esse remedium, vel ad mala avertenda, vel ad doemones fugandos, aut tutissimam viam ad bonorum consecutiouem, quae sibi augurabatur. Fuit hic plumbeus liber repertus in antiquo Sarcophago, in quo cineres demortui fuerant inclusi. Constat autem ex pluribus monumentis, ab Aethnicis praecipuè Aegyptiis non rarò in sepulchris aliqua deposita fuisse, quae ad placandos Manes, vel ad Doemones fugandos utilia esse opinabantur. Ex Cornelio Tacito Annal. lib. 2. habemus, cum refert Mortem Germanici veneno interfecti, Carmina, & devotiones, & nomen Germanici, plumbeis tabulis insculptum, semiusti cineres ad tube obliti, aliaque maleficia, & animas Numinibus infernis sacrari. Ubi notat Ludovicus Dorleans in suis novis cogitationibus, Antiquos plumbeis laminis usos esse, ne facilè illa nomina delerentur.

Case of lead shown in Figure 60. in the form of a compact book, in which seven lead plates are also included, and in each of the many characters are incised along the back, and certainly not one language, but many languages; selected, for they are some of the Greek alphabet, some, indeed, from the Hebrew, many of the ancient Etruscans, but various from the Latin. The character combinations form unintelligible words, which is neither Greek nor Hebrew nor Latin talk, although [even the] highly skilled could never understand. On individual plates there are also added some symbols, but none of them can be deduced, what was conceived in the artist’s mind, what they indicate. For this reason, I judge this to be in the genus of talismans of enumerating, in which is expressed the superstitions of the ancients, that the erroneous conceived in his mind, which he thought to be the best remedy, or to avert evils, or to scare away demons, or the safest way to secure good things, which was prophesied for himself. In this case the leaden book was found in an ancient sarcophagus, in which the ashes of the deceased had been shut up. But it is evident from many tombs, especially from Egyptian pagans who not infrequently deposited in their tombs, that which might placate ghosts, or that which they deemed useful to scare away demons. From Cornelius Tacitus Annal. lib. 2. we have, concerning the death of Germanicus slain by poison, incantations and spells, and the name of Germanicus inscribed on leaden tablets, half-burnt cinders smeared with blood, and other horrors by which in popular belief souls are devoted to the infernal deities. 10 Where in the notes to Louis D’Orleans “New Thoughts”,14 the ancients used plates of lead, to avoid that those names would be wiped out easily.

-

Bernard de Montfaucon, L’antiquité expliquée et représentée en figures. Paris, 1722. Tome II. p. 378-380.

Il me reste à parler d’un petit livre tout de plomb, que j’achetai à Rome en 1699. & dont je fis present à M. le Cardinal de Bouillon : il est de la même grandeur qu’il est ci-après représenté dans la planche; non seulement les deux plaques qui sont la couverture, mais aussi tous les feuillets au nombre de six, la baguette inserée dans les anneaux qui tiennent aux feuillets, la charniere & ses clous; enfin tout sans exception est de plomb. Les douze pages que sont les deux côtez de chaque feuillet, ont autant de figures des Gnostiques: au-dessous de ces figures, il y a des inscriptions, partie Hetrusques et partie Greques, mais aux quatre premieres pages seulement; toute ces inscriptions sont également inintelligibles. La premiere figure est d’un homme nu, qui porte une main à la bouche, & tient l’autre sure le flanc: la seconde represente un homme vêtu qui éleve une main: dans la troisiéme on voit un homme vêtu d’une robe, qui étend ses mains, & qui paroit même les avoir jointes, comme pour prier: la quatriéme, est à tête d’oiseau: la cinquiéme montre un homme à tête de coq, qui a des serpens pour jambes, & qui tient un fouet à la main: nous en avons vû beaucoup de cette maniere: la sixiéme, est un homme à tête d’oiseau, qui a le corps tout raionnant: la septiéme, un buste de Serapis avec le boisseau ou le calathus sur la tête: la huitiéme, une femme étendue à terre: la neuviéme, une figure Egyptienne qui semble une insecte: la dixiéme, une grenouille: l’onziéme, un oiseau qui ressemble à une oie: la douziéme, une femme qui étend un grand voile tout parsemé d’étoiles: j’ai déja dit mon sentiment sur ces figures, dans la Paléographie Greque, p. 182. J’expliquerai ici de nouveau ma pensée en peu de mots. Je crois que ces douze figures marquent ici les douze heures du jour: l’homme nu qui sort du lit, marque la premiere: l’homme tout raionnant à tête d’oiseau, la sixiéme qui est le midi, où le Soleil est dans sa plus grande force; & la femme au voile tout chargé d’étoiles marque la douzieme heure ou le commencement de la nuit, comme nous l’avons prouvé au premier tome: les autres heurs ne sont pas si marquées: mais il faut observer que Serapis qui est à la septiéme heure, est appellé par les Anciens ἑπταγρἀμματος θεός, le dieu à sept lettres, parce qu’il y en a tout autant dans le nom de Serapis ou Sarapis; & c’est apparemment à raison de ce nombre de sept qu’on l’a mis ici le septiéme, pour marquer la septiéme heure. Les Basilidiens qui rapportant tout au Soleil, comptoient 365. puissances ou anges qui avoient rapport à autant de jours de l’année, avoient aussi leurs anges & leurs figures, pour marquer les heures du jour. Le P. Bonanni dans son Museum Kirkerianum a donné la figure d’un livre semblable, trouvé dans un ancien tombeau. La couverture, dit-il, & les sept feuilles dont il est composé, sont de plomb; dans chacune des feuilles il y a des lettres gravées, les unes Greques, les autres Hebraïques, les autres Hetrusques, ou Latines. Ces inscriptions, dit-il, sont inintelligibles: à chaque feuille il y a des figures, dont on entend aussi peu la signification que celle des inscriptions. Le P. Bonanni cite un passage de Tacite, où il est parlé de semblables Tabletes de plomb: il n’a donné que la figure de deux feuillets & de la couverture, telle que nous la représentons. Je persiste a dire que ces livres de plomb sont des restes de superstition des Gnostiques: j’ai pourtant peine à croire qu’on doive les attribuer aux anciens Basilidiens du second siecle; je crois plûtót qu’ils sont d’un siecle posterieur, y aiant toute l’apparence possible que ces superstitions n’auront pas cessé tout d’un coup, mais se seront éreintes peu à peu; c’est le sort ordinaire de toutes les sectes.

It remains to speak of a little book all of lead, which I purchased in Rome in 1699 and of which I made a present to M. le Cardinal de Bouillon: it is the same size it is shown below in the plate; not only the two plates with the cover, but also all the leaves which total six in number, the “baguette” inserted into the rings that holds the leaves, the hinge and its pins; finally all of this is lead without exceptions. The twelve pages are the two sides of each leaf, having Gnostic figures: below the figures, there are inscriptions, part Etruscan and part Greek, but only on the first four pages; all the inscriptions are equally unintelligible. The first figure is a nude man, who holds a hand to his mouth, & keeps the other on his leg: the second shows a clothed man who raises a hand: in the third one see a man wearing a robe, who extends his hands, and even appears to have them clasped, as if in prayer: the fourth, is a bird’s head: the fifth shows a man with the head of a rooster, who has snakes for legs, and who is holding a whip in his hand: we have seen many in this manner: the sixth, is a man with the head of a bird, who has a radiant body: the seventh, a bust of Serapis with a bucket or basket on his head: the eigth, a woman the size of the earth: the ninth, an Egyptian figure which resembles an insect: the tenth, a frog: the eleventh, a bird that looks like a goose: the twelfth, a woman who extends a large veile all sprinkled with stars: I have already expressed my sentiments about these figures in Paléographie Greque, p. 182. I will explain my thoughts here again in a few words. I believe these twelve figures mark here the twelve hours of the day: the naked man who gets out of bed, marks the first: the radiant man with the head of a bird, the sixth which is noon, when the sun is in its greatest strength; and the woman with the veil full of stars marks the twelfth hour or the beginning of the nigh, as we proved in our first volume: the other hours are not so marked: but it must be noted that Serapis is at the seventh hour, who is called by the ancients: ἑπταγρἀμματος θεός, the god with seven letters, because there are just as many in the name Serapis or Sarapis; it’s apparent to reason that this number of seven has been placed here the seventh, to mark the seventh hour. The Basilidians who reported always of the sun, they reckoned 365 powers or angels who were rationed as many days of the year, they also had their angels and figures, to mark the hours of the day. P. Bonanni in his Musaeum Kircherianum gave the figure of a similar book, found in an ancient tomb. The cover, he said, and the seven sheets of which it is composed, are lead; in each sheet there are engraved letters, some in Greek, others in Hebrew, still others Etruscan or Latin. These inscriptions, he said, are unintelligible: on each sheet there are figures, one hears also little of the meaning of these inscriptions. P. Bonanni cites a passage of Tacitus, where he spoke of similar lead tablets: [Bonanni] gave only the figure of two sheets and a cover, such as we present. I persist in saying that these lead books are the remains of the superstition of the Gnostics: yet I can hardly believe that we attribute them to ancient Basilidians of the second century; rather, I think they are from a later century, they have all the possible appearance that these superstitions have not stopped suddenly, but were gradually exhausted; as is the usual fate of all sects.

-

Jacques Matter, Histoire critique du gnosticisme,: et de son influence sur les sectes religieuses et philosophiques des 6 premiers siècles, Vol. 3. Paris: Levrault, 1828. p. 80.

[Planche VI.] Figures 7 et 8. Deux variétés de ma même espèce, que nos plaçons l’une à côté de l’autre, afin de faire voir la latitude que se donnaient des gnostiques, essentiellement indépendans, tout en reproduisant le même monument. Le premier de ces monumens est un plomb, que possède M. Creuzer, qui a bien voulu nous en donner un dessin. Ce qui en constitue la rareté, c’est qu’il est en métal, tandis que la plupart des monumens gnostiques sont en pierre. Je n’en ai pas vu d’autre en métal. Il est vrai que Montfaucon mentionne et décrit un livre de plomb, qu’il attribue aux basilidiens et qu’il explique d’une manière très-ingénieuse;15 mais l’exécution de ce monument est si grossière, si excessivement barbare, qu’il ne peut dater que d’une époque de décadence, qui le met en dehors de la cause gnostique.16 Le monument qui nous occupe est également d’un travail secondaire, et nous avons à reprocher à notre dessinateur, en cette seule occasion, de l’avoir fait trop bien; cependant on n’en doit pas comparer l’exécution à celle du livre de plomb. L’une et l’autre des compositions dont il s’agit, donnent les mêmes noms, ceux de Michaël, Gabriel, Ouriel, Raphaël, Ananaël, Prosoraïel, Yabsaël. La seconde, depuis long-temps connue, se trouve dans la plupart des collections de pierres gnostiques.17

[Plate VI.] Figures 7 and 8. Two varieties of the same type, which we place one next to the other, in order to see the flexibility the gnostics gave themselves, essentially independent, while reproducing the same monument. The first of these monuments is a lead, possessed by M. Creuzer, who was kind enough to give us a drawing. What makes it rare is that it is metal, while most gnostic monuments are in stone. I have not seen another in metal. It’s true that Montfaucon mentions and describes a book of lead, which he attributes to the Basilidians and that he explains in a very ingenious manner, but the execution of this monument is so shoddy, so excessively barbaric, that it can not date from an age of decadence, which puts it out of the gnostic cause. The monument before us is a secondary work, and we fault our artist, on this occasion, to have done too well; however we do not compare the execution with that of the book of lead. Both compositions in question give the same names, those of Michael, Gabriel, Uriel, Raphael, Ananael, Prosoraiel, Yabsael. The second, known for a long time, is found in most collections of gnostic stones.

-

Giuseppe Brunati, Musei Kircheriani inscriptiones ethnicae et christianae, 1837. p. 122.

De Mus. Kirch. Libello Basilidiano Plumbeo Opistographo Dissertatiuncula

De libello disseram plumbeo Basilidiano, qui septem constans aeneis pagellis ex utraque parte scriptis figurisque anaglyptis in fastigio insignitis, atque operculo figuris ornato protectus, in Museo Kercheriano servatur. Utinam vero authenticus sit. Libellus iste diversus est ab alio pariter olim Kircheriano edito a Bonannio,18 et exinde a Montfaucon:19 eoque magis differt ab alio hujus generis libello edito a Montfauconio ipso.20 Septem quidem tabellis, uti hodiernus Kircherianus libellus, sic et alius editus a Bonannio constabat, eratque et ipse operculo, figuris anaglyptis ex utraque parte insignito protectus, forma item litterarum, atque stylus figurarum variis in tabellis idem erat. Ast non eadem litterarum disposito, non eadem repraesentationes: unde quod duo sint libelli, non unus, clare patet. Tantum suspicio oritur, quod quidam, abrepto sincero veteri libello, alium fraudolenter substituerit. Alius huiusmodi libellus a Montfaucon unice, quod noverim, editus, a duobus Kircherianis mox descriptis, et numero paginarum, quae sex tantum sunt, et scripturae ratione quae in quatuor tantum paginis, et in una tantum, non in utraque earum, facie est, diversus. Ast consonat omnino litterarum forma, et figurarum, quibus tabellae insignitae sunt, stylus. Forsitan vero iste Montfauconii libellus una pagella deficiens erat. Ex omnibus dictis argui potest, quod tres libelli (supposito genuino et hodierno Kircheriano) ex eadem officina eodemque tempore prodierint, atque eodem systhemate fuerint consarcinati. Hisce praepositis, si Nonnum Panopolitanum21 de quodam septem paginarum libello disserentem audimus, tres supra descriptos libellos fatalitios fuisse vel talismanicos faciliter argumentari possumus. Ad quam rem exponendam etiam Taciti22 verba erunt non inutiliter advocanda. Scribebat enim ipse: “Reperiebantur . . . . carmina et devotiones et nomen Germanici plumbeis tabellis insculptum, semiusti cineres ac tabe obliti, aliaque maleficia, quis (pro queis aut quibus) creditur numinibus infernis sacrari.” Nedum vero impie, sed etiam stulte Dupuis23 confert libellum, de quo disseruit Nonnus, oum libro “septem sigillis” munito quem S. Joannes24 describit. Praeter quam quod enim “septem sigilla” non idem sunt ac “septem pagellae”, omnia etiam alia discordant. Sed Depuisii phantasiae insaniendo assuetae, ingenioque dissonantia ac toto coelo differentia componendo facili, discrepantiae hujusmodi se se non offerebant. De hac re agam et alibi.25 Nonni Dionysiaci fatalitius liber, atque tres plumbei superius descripti libelli, differunt a “tabulus coeli”, de quibus quidam veteres loquuntur, puta Philostratus,26 Plotinus,27 et Origenes.28 “Tabulae coeli” enim non erant nisi coeli ipsi, sive stellae et planetae, in quibus hominum fata legi dictitabant astrologi. Ut auctores et tempus trium libellorum plumbeorum aliquomodo innotescat, animadvertendum est ad litteras etruscas, quas in ipsis cum litteris graccis, et signis astrologicis seu litteris quibusdam Aegyptiacis commixtas intuemur: exunde deduci poterit libellos hujusmodi scriptos in Etruria fuisse, uti aestimabat Montfaucon, atque secundo vel tertio forsitan saeculo. In Etruria porro, litterae graecae, signa illa astrologica a veteribus Aegyptiorum schematibus desumpta, atque Etruriae ipsius veteres litterae, notae adhuc illo tempore, saltem doctis, erant. Ex aliis rebus animadversis collatisque Montfauconius idem non sine veritatis specie arguebat, quod auctores libellorum illorum Gnostici fuerint sive Basilidiani in Etruria degentes. Porro Basilidiani has litterarum uniones, quorum systhema nobis adhuc omnimode fere latet, suis in documentis, quorum innumera extant edita et inedita, diligebant. Ab illius autem temporis sive saeculi secundi aut tertii stylo in libellis, de quibus agimus, litterarum graecarum atque etruscarum forma non dissonat. Basilidianum fuisse et scriptorem illum Tyrrhenum sive Etruscum, ex cujus libro “de Cosmogenia” fragmentum attulit Svidas (V. Τυρρηνια), ex nonnullis argumentis ipse arguo.29 Montfauconius adhuc conatus est exponere systhema figurarum quibus insignitus erat plumbeus ille libellus ab ipso, uti dixi, unice editus, putavitque in iis “horas” repraesentari. Ast videant docti, an ejus expositio probanda sit. Ego et quoad figuras et quoad litterarum Graecarum, Etruscarum, et Aegyptiarum, quibus ornati sunt omnes tres libelli, interpretationem, me “Davum” esse fatear.30 Usus autem plumbearum tabularum ad scripturam jam antiquitus erat apud populos Romano dominio subjectos aliosque, uti constat ex Pausania,31 ex Svetonio,32 ex Frontino,33 ex Dione,34 ex Plinio,35 atque ex Tacito.36 Sileo in hanc rem verba Job IX, 24, quia diverso modo, ac habet Vulgata, exponi poterunt ex originali textu.

I speak of a Basilidian lead book, which consists of seven copper pages with writings and figures in relief marked on the top of both sides, and figures adorning the protecting cover, preserved in the Museo Kercheriano. Would that it be authentic. This little book is different from the other formerly in the Kircherian published by Bonanni as well, and furthermore by Montfaucon: in fact it differs more from the other book published by Montfaucon. Seven of the tablets, to make use of the current Kircherian little book, so this and the other published by Bonanni consisted, and it was the same lid, decorated with figures in relief on both sides, for protection, likewise the form of the letters, and the style of the figures of the different parts of the tablets was the same. Yet it is not designed with the same letters, it is not the same representations: hence the fact that they are two books, not one, is clearly evident. So the suspicion arises that this is some genuine old book, fraudulently substituted for another. Another little book of this kind by Montfaucon, that he had known, was published (from the two the Kircherian described soon after), and the number of pages which are only six, and writing in only four of the pages, which, in the one and only, but not in both of them, the face is different. But in harmony with the form of all the letters, and the figures, endowed with all these documents are marked, with a stylus. Perhaps, however, this book is really Montfaucon’s with one page missing. Out of all what has been said it can be argued, that there are three little books (supposing today’s Kircherian is genuine) at the same time, from the same method, and the same system they are patched together. In these above, if Nonnus of Panopolis of a certain seven page book heard arguments, that the three books described are curses or talismanic is easily arguable. And to this explanation the words of Tacitus, too, will be not useless to setting forth the argument. He wrote, for he says himself, “could not understand. . . . incantations and spells, and the title of Germanicus engraved on the tablets of lead, ashes and gore semiusti have forgotten, and other horrors, a man (to whom or for whom) is believed to be the infernal deities. “10 Instead of the wicked, but also foolishly Dupuis23 brought together books, of which he argued Nonnus, mocking the book of “seven seals” shielded which St. John24 describes. Besides the fact that, for the “seven seals,” is not the same as the “seven pages”, all other things are in disagreement. But Dupuis’s usual mad fantasies, to temper the discrepancies and totally different composition easily, such discrepancies have not offered themselves. On this subject, I will discuss elsewhere. Nonnus’s irreproachable book Dionysiaca, and the three little lead books described above, differ from the “tables of heaven”, of some old sayings, for instance, Philostratus,26 Plotinus,27 and Origen.28 “Tables of the heavens,” it is not, but for the heavens itself, or the stars and planets, astrologers asserted that the fates of men are written. As to knowing in some way the authors and times of the three lead books, we observe that the letters of the Etruscans, which are mixed in with Greek letters and astrological signs or Egyptian letters, we see: we can deduce books in similar scripts from Etruria, in the estimation of Montfaucon, from the second, perhaps the third century. In Etruria, however, Greek letters, astrological signs drawn from the drafts of the ancient Egyptians, and the Etrurian letters of the same antiquity, were well known yet at that time, or at least they were learned. Having observed the same from others, Montfaucon formulated (not without truth) the particuluar argument, that the authors of these books were Basilidians or Gnostics living in Etruria. Further, these singular Basilidian documents, whose system is to us still almost totally hidden, in the documents, whose innumerable extent, published and unpublished, I regard. While those of the time or age of the second or third [century] with the style of a book, of which we speak, Greek and Etruscan literature does not disagree with the form. Basilidians and writers, whether Tyrrhenian or Etruscan, from the fragmentary book “of Cosmogenia” in Suidas (V. Τυρρηνια), out of this come some of the arguments he argues.29 Montfaucon still tried to explain the system of figures which decorated his leaden book, as I have said, his high decree, his belief that these represented “hours”. But in the consideration of the learned, an explanation will be proven. I too, as long as figures and Greek, Etruscan, and Egyptian letters, which decorate all the books, mean “Davum” to me I admit.30 Now the use of lead tablets for writing in antiquity existed under the dominion of the Roman people, as is evident from Pausanias,31 from Suetonius,32 from Frontino,33 from Dio,34 from Pliny,35 and from Tacitus.36 The words of Job 9:24 remain silent in this matter, because of the difference after the manner that has the Bible, out of the original will be able to be explained in the text.

-

Jacques Matter, Une excursion gnostique en Italie. Strasbourg, 1852.

En attendant le rétablissement de la collection des abraxas du Vatican, celle du Collegio romano, anciennement dite Museum Kircherianum, est la seule qui soit publique. Elle se compose: 1.° de onze pierres gravées; 2.° d’un clou en fer; 3.° d’une phalera romana en agate saphirine, du temps des Antonins, et sur laquelle on retrouve les mots: Michael, Raphael, Ouriel, Sabaoth, Abrasax, Emanouel; 4.° d’une lamelle d’argent chargée d’une inscription; 5.° de sept lamelles de plomb qui forment un ensemble ou un cycle de représentations et d’inscriptions. Les pierres gravées, fixées à une vitrine, mais d’une manière mobile, sont connues par les empreintes d’Odelli et n’offrent rien de particulier. Le clou de fer est chose curieuse et rare en ce qu’il porte le symbole assez fréquent et peu expliqué de la grenouille. (Voir la grenouille sur un autel : Table isiaque de Montfaucon, Antiquité expliquée, t. IV, p. 340; la grenouille dans une fleur de lotus, ibid., p. 348; des divinités à tête de grenouille, Guigniaut, Relig. de l’antiquité, pl. XXXII, fig. 141; la grenouille du livret de plomb, dont il sera question ci-dessous.) La lamelle d’argent est encore une chose curieuse et rare. On a peu de ces monuments. Je ne connais que la lamelle plus ou moins gnostique du Musée de Carlsruhe, publiée par Preuschen, puis par Kopp,37 et celle qui m’occupe et qui n’était pas encore publiée, quand je la vis, mais qui vient de l’être à Naples , dit-on. En fait de lamelle de plomb, on ne citait jusqu’ici que les deux livrets dont Montfaucon parle d’une manière assez inexacte dans sa Paléographie grecque (p. 182) et dans son Antiquité expliquée (t.IV, p. 379). De ces livrets, l’un qui était tombé entre ses mains à Rome et qu’il donna au cardinal de Bouillon, mort à Rome, en 1715, dans la disgrâce et dans un dérangement de fortune, a disparu, sans qu’on sache ce qu’il peut être devenu. L’autre est précisément celui dont je parle et dont Montfaucon assure que Buonanni a publié, dans son Museum Kircherianum, la figure de deux feuillets et de la couverture. Mais il y a là une singulière erreur. De tout ce qu’a publié Buonanni et de ce que reproduit Montfaucon, rien ne ressemble aux sept feuillets que j’ai eus entre les mains, que j’ai copiés et comparés plus d’une fois avec les dessins des deux savants. D’abord, les deux feuillets publiés par eux donnent des figures qui ne se trouvent pas sur ceux du Museum romanum. Ensuite ils donnent au bas de ces figures quatre lignes d’inscriptions, tandis que les feuillets que j’ai copiés en ont toujours cinq. Puis ces inscriptions ne sont pas les mêmes. Enfin, mes sept feuillets n’ont pas de couverture que je sache, et n’ont jamais été engagés dans une charnière. Je puis donc affirmer positivement que la publication des deux antiquaires, si authentique ou si exacte qu’elle soit, ce que je ne juge pas, n’est pas du tout celle des sept feuillets de plomb dont j’ai dû la communication à l’obligeance du Rév. P. Marchi. Mais je dois ajouter que les figures et les caractères ont de grandes analogies avec ceux des douze dessins du monument donné par Montfaucon au cardinal Bouillon et publié par l’illustre archéologue. Toutefois, il y a de grandes différences aussi entre les deux ordres d’inscriptions et de figures; voir mes planches III à IX, où je publie les sept feuillets. Au premier aspect, je vis d’abord un monument du gnosticisme ancien et véritable dans les sept lamelles en question et qui ne forment pas un livret, mais qui sont si parfaitement conservées que peu de traits vous en échappent, quoiqu’il y en ait de fort mal exécutés. Plus tard, je suis un peu revenu de cette opinion, mais il n’en est pas moins à désirer qu’il en soit fait une étude plus approfondie. L’interprétation complète de ces singuliers feuillets donnera probablement un nouvel intérêt à l’histoire du syncrétisme religieux, si non des premiers siècles de notre ére, du moins d’une époque un peu postérieure. Du moins, si ce travail appartient à une école gnostique, c’est à une de celles qui se sont le plus éloignées de la pureté et du berceau du Christianisme. On y remarque toute une série de symboles qui ne se retrouvent pas sur d’autres monuments gnostiques. Plusieurs des figures semblent en rappeler d’autres ou offrir de l’analogie avec elles, il est vrai; toutes, cependant, ont des caractères qui leur sont propres et qui semblent en faire un nouvel ordre de monuments. En effet, nous voyons ici un symbolisme si nouveau qu’il se rattache à peine par quelques points à celui qu’on reconnaît pour gnostique. Le premier feuillet (pl. III) présente deux personnages, l’un sans vêtement, l’autre court vêtu, un trident sur l’épaule et accueillant le premier avec un geste de surprise. L’inscription, placée au-dessous de la scène, en mettait sans doute le sens à la portée des initiés. Faite en caractères grecs, latins et étrusques, et offrant plus de consonnes que de voyelles, elle est pour nous inintelligible. Au revers du feuillet se voit une espèce de palmier en forme de globe et à côté une double guirlande portée par une tige garnie d’ailes. On dirait les symboles de la gloire et de l’élévation réservée à ceux qui entreprennent résolument et achèvent avec courage la carrière des épreuves et des combats de la vie terrestre. Le second feuillet offre, au recto, un personnage en robe longue en adoration contemplative devant un oiseau; au verso, un personnage non vêtu, en face d’un petit quadrupède en forme de momie (pl. IV). Le troisième feuillet (pl. V) montre une tortue contemplée avec déférence par un homme effacé dans mon dessin; et au revers un personnage élevé sur une colonne, les yeux fixés aux cieux, adoré par une femme. Au quatrième feuillet se retrouve la tête de grenouille, sortant d’un corps qui semble figurer la terre, et suivie ou surveillée par un voyageur en manteau court, à tète d’Anubis (pl. VI), personnage connu par d’autres monuments.38 Le revers nous montre une femme cheminant, appuyée sur un bâton et reçue par un personnage en robe ornée et qui semble l’inviter à avancer. Suit au feuillet cinquième un homme qui présente à l’Abraxas, ayant la tête de lion, un objet ou un symbole à peine indiqué et au revers une grenouille (emblème de quelque théorie métempsychologique), en face d’un serpent, qui est l’emblème du génie Agathodémon. Au-dessous de la première des deux scènes se lit distinctement le mot Jao (pl. VII). Au feuillet sixième, un personnage dont le buste est radié, se trouve en face d’un monstre marin ailé, et semble vouloir l’apaiser par un présent qu’il tient à la main. Le revers présente un petit personnage d’une grotesque gravité, la tête décorée du modius, et plus loin, sans rapport apparent, un corps-momie prenant des ailes en forme de croix, au-dessus de laquelle se voit une tête, tandis qu’au bas se lit le mot χεφαλου. Enfin, le septième feuillet offre de nouveau un personnage humain, mi-habillé et mi-couché, en face d’un oiseau qu’il regarde en avançant des bras à peine indiqués, et au revers un personnage à tête de vieillard plutôt que de jeune femme, retenant du bras droit une sorte d’écharpe sur sa tête et rappelant par sa pose la Nuit étoilée des monuments grecs, ayant à sa gauche un taureau assez bien dessiné en peu de traits. Au-dessous, dans l’inscription, se voit le signe planétaire de Jupiter, et n’était la tête de vieillard, l’espèce de bâton sur lequel s’appuie le personnage à écharpe ou tunique volante, on serait tenté d’y voir la belle Europe. En l’état actuel, l’explication de ces feuillets est encore hérissée de difficultés telles qu’il ne faut pas même la tenter. Montfaucon, qui voyait dans ses six feuillets douze dessins ou douze scènes, terminées par une figure qui semblait être la nuit, y vit les douze heures du jour avec les incidents qu’elles semblent amener dans la vie de l’homme. Les scènes étant au nombre de quatorze et ne se prêtant pas à l’hypothèse des douze heures du jour, il n’en peut plus être question. J’ai émis au sujet de quelques symboles l’hypothèse d’une représentation relative à la migration des âmes et à la métempsychose, thèmes favoris de certains artistes du gnosticisme; mais, en l’état actuel, cette hypothèse n’est qu’une de celles qui ont pour but d’en provoquer d’autres, et tel est aussi le motif qui m’a décidé à publier mes dessins dans les circonstances présentes. Elles sont peut-être très-favorables. D’après Buonanni, ces plombs ont été trouvés dans des tombeaux, et près de Rome sans doute. Or, on vient précisément de faire d’autres découvertes qui semblent s’y ajouter, comme pour y répandre quelque jour. …39 Puis l’ordre d’idées, d’emblèmes et de légendes qu’offrent les feuillets de plomb de la Via Appia diffèrent bien plus encore de ce que nous présentent les lamelles de plomb ou d’argent du Collegio romano et du Musée de Carlsruhe. Enfin cela diffère de toutes les scènes qui figurent sur les feuilles si curieuses des deux livrets gnostiques dont l’un a été publié par Montfaucon et dont nous reproduisons l’autre. Le tout se distingue des autres représentations gnostiques par une grande sobriété dans le symbolisme et par l’absence complète de quelques-uns des emblèmes familiers à ces syncrétistes. Il en résulte qu’on ne peut rattacher ces plombs d’une façon directe à aucune des catégories énumérées d’entre les monuments classés en archéologie, etqu’il faut les mettre provisoirement dans une classe spéciale. Aussitôt qu’ils auront été publiés, et j’espère en élever l’appréciation par les faibles échantillons que j’en donne, on verra qu’une veine nouvelle vient d’être ouverte pour l’archéologie religieuse de cette époque d’enfantement d’un monde nouveau et de transformation d’un monde vieilli. Une commission spéciale vient d’être nommée pour proposer au gouvernement pontifical l’organisation d’un Musée chrétien; j’ignore si les feuilles en question doivent y entrer; mais la réunion dans ce dépôt de tout ce que peuvent fournir les fouilles déjà faites et à faire encore dans les tombeaux et dans les catacombes, répandre peut-être sur ces plombs un jour tout nouveau. J’ajouterai maintenant que j’ai envain recherché à Rome la trace du livret de plomb publié par Montfaucon, et que j’ai lieu de croire qu’il n’y existe plus. S’il s’y était conservé, on le trouverait, je crois, soit dans ces collections particulières qu’y entretiennent quelques-unes des grandes maisons, soit chez les marchands d’antiquités. Je suis certain qu’il ne se trouve pas chez ces derniers.

Pending the restoration of the collection of abraxas of the Vatican, the Collegio Romano, formerly called the Museum Kircherianum, is the only one that is public. It consists of: 1.° eleven engraved stones; 2.° an iron nail; 3.° a Roman phalera in saphirine agate, from the time of the Antonines, on which we find the words: Michael, Raphael, Uriel, Sabaoth, Abraxas, Emanouel; 4.° a silver plate loaded with an inscription; 5.° seven lead plates that form a set or cycle of representations and inscriptions. The engraved stones, attached to a cabinet, but in a movable manner, are known by the imprint of Odelli and offer nothing special. The iron nail is curious and rare in that it carries the symbol fairly frequently explained as being of the frog. (See the frog on an altar: Table of Isis of Montfaucon, Antiquity expliquée, t. IV, p. 340; the frog in a lotus flower, ibid., p 348; frog-headed deities, Guigniaut, Relig. de l’antiquité, pl. XXXII, fig. 141; the frog lead booklet, which will be discussed below) The plate of silver is also a curious and rare thing. There is little of these monuments. I only know of the plate more or less Gnostic of the Karlsruhe Museum, published by Preuschen then by Kopp, and the one before me and was not yet published when I saw her, but that comes from being in Naples, they say. Indeed of lead plates, one cites the two booklets which Montfaucon speaks of in a relatively inexact manner in his Paléographie grecque (p. 182) and in his Antiquité expliquée (t.IV, p. 379). Of these booklets, one that had fallen into his hands in Rome and which he gave to the Cardinal de Bouillon, who died in Rome in 1715, in disgrace and in a disruption of fortune, has disappeared, no one knows where it can be found. The other is precisely that of which I speak and which Montfaucon ensures Buonanni published in his Musaeum Kircherianum, the figure of two leaves and the cover. But there is here a singular error. From all that has been published by Buonanni and what Montfaucon reproduced, nothing resembles the seven sheets that I had in my hands, I copied and compared more than once with the designs of these two scholars. First, two sheets published by them give figures which are not found on those of the [Kircherian]. Then they give at the bottom of these figures four lines of inscriptions, while the leaves I copied always have five. Thus, these inscriptions are not the same. Finally, my seven sheets do not have a cover as far as I know, and have never been engaged in a hinge. So I can positively say that the publication of these two antiques, whether authentic or correct, I do not judge, is not at all that of these seven lead sheets which I had by the kindness of rev. P. Marchi. But I must add that the figures and characters have great similarities with those of the twelve drawings of the monument given by Montfaucon to Cardinal Bouillon and published by the famous archaeologist. However, there are also major differences between the two kinds of inscriptions and figures; see my boards III to IX, where I have published the seven leaves. At first sight, I first saw a monument of ancient and true Gnosticism in the seven subject slats and do not form a booklet, but are so perfectly preserved as few strokes as you escape, though there are of badly executed. Later, I’m a little income from this opinion, but it is no less to be desired that it be done further study. The complete interpretation of these singular sheets probably give a new interest in the history of religious syncretism, if not the first centuries of our era, at least for a time a little later. At least, if the work belongs to a gnostic school, is one of those who are most distant from the purity and the cradle of Christianity. One notices a series of symbols that are not found on other Gnostic monuments. Many of the figures seem to recall others or offer an analogy with them, it is true; All, however, have their own character and seem to make a new order of monuments. Indeed, we see here a symbolism so new that it relates by only a few points to that which we recognize for Gnostic.

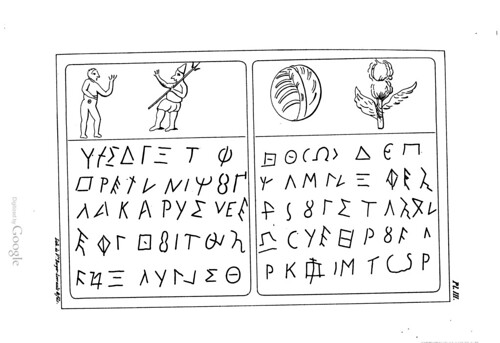

The first sheet (Pl. III) has two people, one without clothes and the other dressed in shortclothes, a trident on the shoulder and welcoming the first with a gesture of surprise. The inscription placed beneath the scene, probably puts the meaning within the reach of initiates. Made in Greek, Latin and Etruscan characters, and offering more consonants than vowels, for us it is unintelligible. On the reverse side of the sheet is seen a species of palm tree in the shape of a globe and next to it a double garland carried by a rod topped with wings. It looks like the symbols of glory and elevation reserved for those who resolutely undertake and complete with courage the career of trials and struggles of life on earth.

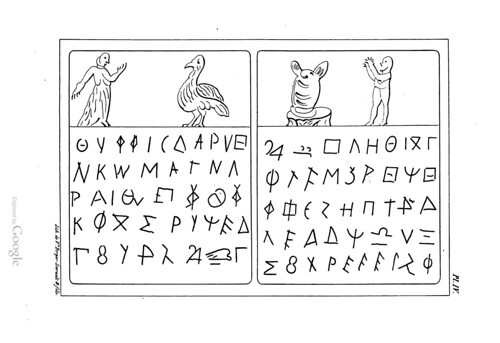

The second sheet has on the front, a character in a long dress in contemplative adoration before a bird; on the back, a naked character in front of a small mummy-like quadruped (pl. IV).

(Pl. V) The third sheet shows a turtle contemplated with reverence by a man erased in my drawing; and on the reverse a person elevated on a column, eyes fixed to heaven, adored by a woman.

In the fourth sheet is found the head of a frog, out of a body that appears to be included in the earth, and followed or monitored by a traveler in a short cloak, with a head of Anubis (pl. VI), a character known from other monuments.38 The reverse shows a woman walking, leaning on a stick and received by a character in ornate dress who seems to invite her to move forward.

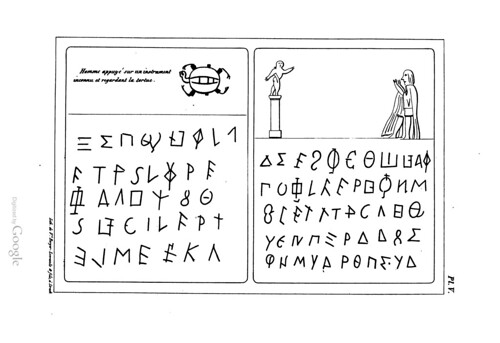

Now on the fifth leaf, a man who presents to Abraxas, having a lion’s head, an object or simply a symbol indicated; and on the reverse a frog (emblem of some metempsychic theory) in front of a serpent, which is the emblem of the genie Agathodaemon. Below the first of two scenes one distinctly reads the word IAO (pl. VII).

In the sixth leaf, a character whose head is removed, who is in front of a winged sea monster, and seems to appease it with a present he holds in his hand. The reverse shows a small figure of a grotesque seriousness, the head decorated with a modius, and further, seemingly unrelated, a mummy body making its wings in the shape of a cross, above which one sees a head, while at the bottom one reads the word χεφαλου.

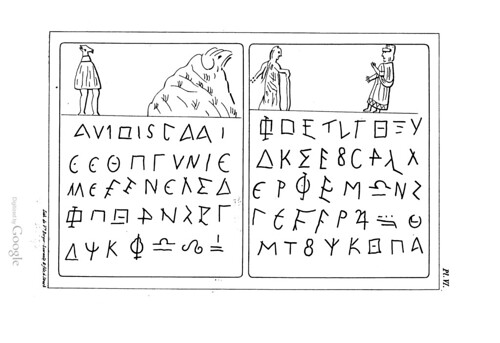

Finally, the seventh sheet provides again a human character, half-dressed and half-lying in front of a bird that looks in front of the arms of the just-mentioned, and on the reverse the head of an old person rather like a young woman, holding in their right arm a kind of scarf on their head and recalling in their pose the Starry Night of Greek monuments, having on their left a fairly well drawn bull in a few lines. Below, in the inscription, one sees the planetary sign of Jupiter, and rather than the head of an old person, with the sort of rod on which is resting the character with the flying scarf or coat, one is tempted to see the beautiful Europa. As it stands, the explanation of these sheets is still bristling with difficulties such that we should not even try. Montfaucon, who saw in his six sheets twelve drawings or twelve scenes, terminated by a figure who seemed to be the night, saw the twelve hours of the day with incidents they seem to bring in the man’s life. The scenes here are fourteen in number and do not lend themselves to the assumption of the twelve hours of the day, it is out of the question. I’ve expressed about some symbols the hypothesis of a representation relating to the migration of souls and of metempsychosis, favorite themes of artists of Gnosticism; but in its current state, this hypothesis is only one of those that are intended to provoke others, and this is also the reason I decided to publish my drawings in the present circumstances. I hope that they may be very favorable. According to Buonanni these lead [leaves] have been found in tombs, doubtlessly near Rome. Now, it is precisely some other discoveries that to this seem to be added, as if to throw some light on the matter. […] 39 The order of ideas, symbols, and legends offered by the lead sheets of the Via Appia are very different from what we have presented for the the strips of lead or silver in the Collegio Romano and the Museum of Karlsruhe. Finally it differs from all the scenes which appear on the leaves of both of the curious Gnostic books, one of which was published by Montfaucon and of which we reproduce the other. All are distinguished from other Gnostic representations by a great restraint in the symbolism and the complete absence of some of the familiar emblems of this kind of syncretism. The result is that we can not connect these lead strips directly to any of the categories listed among the monuments in archeology, and they must be put temporarily in a special class. As soon as they are published, and I hope to raise their appreciation by the small sample I give, we will see that a new vein has just been opened for religious archeology of this period of the birth of a new world and the transformation of the ancient world. A special commission has recently been appointed to propose to the papal government the organization of a Christian Museum; I do not know if the leaves in question must enter; but the reunion in this repository of all that provided by the excavations already performed and yet to be done in the tombs and catacombs, will perhaps shed on these lead strips an entirely new light. Now I add that I have sought in vain in Rome traces of the lead booklet published by Montfaucon, and I have reason to believe that it does not exist any more. If it was preserved, it would be found, I believe, in these particular collections which are maintained in some of the great mansions, or in the antique shops. I’m certain you cannot find it among these.

-

Ettore de Ruggiero, Catalogo del Museo Kircheriano, Roma: Coi Tipi del Salviucci, 1878. p. 63-79, no.199.

Libello basilidiano di piombo (al. c. 10, lar. c. 9) La copertura del libro ha sul diritto, in rilievo, un busto di donna velata, sul rovescio quello d’un uomo barbato. Dentro erano, per mezzo di cerniera, riunite sette sottili tavolette di piombo della medesima grandezza, che ora sono sciolte, ciascuna delle quali contiene, ai due lati, incise due figure simboliche nella parte superiore, e una leggenda nel rimanente. Una strana mescolanza di lettere greche, italiche e latine non ne rende possibile alcuna decifrazione; il carattere gnostico dell’insieme è però indubitato. Il Bonanni menziona (mus. Kirch. p. 180), pubblicandone un saggio (tav. LX), un analogo monumento, che pare sia stato ai suoi tempi trovato in Roma, ed era conservato nel Museo. Esso però era affatto diverso dal nostro, come pure dall’altro acquistato in Roma dal Montfaucon nel 1699 e donato da lui al cardinale de Bauillon [sic] (palaeogr. graeca p. 181; cf. antiq. expliq. 2, 2, pl. 177). È ignoto come e quando sia scomparso il primo del Museo, sostituendovisi quest’altro. Il Brunati, (p. 122) per altro, già notò nel 1838 questa sostituzione, manifestando qualche dubbio sulla sua autenticità, e concludendo che tutti e tre i sudetti libelli possano pervenire da una medesima origine.

Basilidian book of lead The cover of the book on the right, in relief, a bust of a veiled woman, on the reverse that of a bearded man. Inside were, by means of zipper, gathered seven thin lead tablets of the same size, which are now dissolved, each of which contains two sides, recorded two symbolic figures at the top, and a legend in the remainder. A strange mixture of Greek letters, Italic and Latin does not make any decryption possible; the Gnostic character of the whole, however, is undoubted. Bonanni mentions (mus. Kirch. P. 180), publishing in an essay (plate. LX), a similar work, which seems to have been found in Rome in his time, and was preserved in the Museum. However, it was completely different from ours, as well as the other purchased in Rome by Montfaucon in 1699 and donated by him to Cardinal de Bouillon (palaeogr. Graeca p. 181; cf. antiq. Expliq. 2, 2, pl. 177). It is unknown how and when it vanished the first of the Museum, replacing (the face of?) this other. Brunati, (p. 122) for one, already noticed in 1838 this replacement, expressing some doubt about its authenticity, and concluded that all three of these books came from the same origin.

-

Ettore de Ruggiero, Guida del Museo Kircheriano, Roma: Coi Tipi del Salviucci, 1879. p. 10.

Libro gnostico di piombo, composto di copertura o teca di sette tavolette scritte ad incisione ai due lati, con figure e simboli superiormente. Una strana mescolanza di lettere greche, etrusche, latine ed ebraiche le rende punto intelligibili. Dall’insieme si scorge il carattere gnostico anche di questo monumento, che non pare abbia altro simile.

Gnostic book of lead, consisting of a cover or reliquary with seven tablets written engraved on both sides, with figures and symbols above. A strange mixture of letters Greek, Etruscan, Latin and Hebrew makes the point unintelligible. You can see from all the Gnostic character too of this monument, which seems to have more such.

-

C. W. King, The Gnostics and their Remains, 2nd ed. London: David Nutt, 1887. p.362-366.

We now come to relics of the same sort [i.e. leaden], but of diverse intention; being those passports to eternal bliss, so frequently mentioned in the course of the preceding dissertation. Of these the most complete example is the Leaden Book formerly belonging to the celebrated Father Kircher, in whose collection it first made its appearance, but concerning the provenance of which nothing is known, although Matter suspects it to be the same that Montfaucon gave to Cardinal Bouillon, who died at Rome in 1715. But this identification is entirely ungrounded, as shall presently be shown. The same writer has given facsimiles, in his ‘Excursion Gnostique,’ of the seven pages composing the book, now deposited in the Museum Kircherianum. These leaves are of lead, 3 × 4 inches square, engraved on each side, with a religious composition for heading, under which are, in every case, five lines of inscription, that mystic number having doubtless been purposely adopted by the spell-maker. These lines are written in large Greek capitals, square-shaped, and resembling the character commonly used on Gnostic gems. Intermixed are other forms, some resembling the hieroglyphs still current for the Signs and Planets; others Egyptian Demotic and Pehlevi letters. The language does not appear to be Coptic, but rather some Semitic tongue, many words being composed entirely of consonants, showing that the vowels were to be supplied by the reader. The chief interest, however, of the relic lies in the designs heading each page, in which we recognise the usual figures of Gnostic iconology, together with others of a novel character, all touched in with a free and bold graver with the fewest possible strokes. The purport of the writing underneath may be conjectured, on the authority of the ‘Litany of the Dead’40 and the ‘Diagramma of the Ophites,’ to be the prayers addressed by the ascending soul to these particular deities, each in his turn. The very number of the pages, seven in all, comes to support this explanation. The Astral Presidents to be propitiated in the heavenward journey are represented in the following manner:–

- A nude female figure, in which the navel (the “circle of the Sun”) is strongly defined: she makes a gesture of adoration to a genius in a conical cap and short tunic, armed with a trident, Siva’s proper weapon, and consequently appropriated afterwards by the mediæval Ruler of Tartarus. Reverse. Palm within a circle or garland, and a large Caduceus.

- Female in flowing robes, addressing a gigantic fowl, much too squat, apparently, in its proportions for the ibis of Thoth: perhaps intended for the yet more divine bird, the phoenix. Reverse. Nude female adoring a certain undefined monster, furnished with large ears, and placed upon a low altar. The first line of the accompanying prayer seems to begin with the Pehlevi letters equivalent to S, P, V.

- Horus, leaning upon an instrument of unknown use, regarding a huge tortoise, better drawn than the rest, which is crawling towards him. Reverse. Female in long flowing robes, holding up her hands to a naked child (Horus?), who is in the act of leaping down to her from a lofty pedestal.

- Anubis attired in a short mantle (reminding one of Mephistopheles) attentively contemplating a lofty hill, the apex whereof has the form of an eagle’s head. Reverse. Female in rags leaning on a staff advancing towards another richly clothed and crowned, who lifts up her hands as though terrified at the apparition.

- Abraxas in his proper form, looking towards a female fully draped, who offers him some indistinct symbol, much resembling an Ε turned upside down. The prayer below opens with the word ΙΑΩ; whence it may be fairly conjectured that the first characters in each of the other pages give the name of the deity pictured above. Reverse. Frog and serpent facing each other: ancient emblems of Spring, but probably used here in their mediæval sense as types of the Resurrection of the body.

- A headless man with rays issuing from his shoulders, and holding out a torch, appears falling backwards with affright on the approach of a winged dragon. Reverse. A squat personage with radiated crown stands in front face in the attitude of the Egyptian Typhon. On the other side stands a very indistinct figure, resembling a Cupid, having square-cut wings, his back turned to the spectator.

- Female with robe flying in an arch over her head, as Iris is commonly pictured, extends her hand to an approaching bull: the drawing of the latter being vastly superior to any of the other figures. One is led to discover in this group Venus and her tutelary sign, Taurus. Reverse. Female reclining on the ground, towards whom advances a large bird, seemingly meant for a pigeon. In the sacred animals figuring in these successive scenes it is impossible to avoid discovering an allusion to the forms the Gnostics gave to the planetary Rulers. A legend of theirs related how the Saviour in his descent to this lower world escaped the vigilance of these Powers by assuming their own form as he traversed the sphere of each, whence a conjecture may be hazarded that similar metamorphoses of the illumined soul are hinted at in these inexplicable pictures. We now come to the consideration of a second relic of the same kind, known as “Card. Bouillon’s Leaden Book.” How Matter could have supposed this to be the same with Kircher’s (supposing him ever to have compared his own facsimiles with Montfaucon’s) is a thing totally beyond my comprehension. For Montfaucon, in his Plate 187, has given every leaf of the former, apparently copied with sufficient fidelity: the pictures on which I shall proceed to describe for the purpose of comparison with those in the Kircherian volume; for the general analogy in the designs attests the similar destination of both monuments, whilst at the same time the variation in details proves the existence of two distinct specimens of this interesting class. The leaves within the two covers, connected by rings secured by a rod passed through them, are only six in number; whilst the inscriptions, though in much the same lettering as the Kircherian copy, fill only four lines on a page, and only four pages in all: the other eight pages having pictures alone. Now to describe these pictures, which seem in better drawing than those of the former set.41 Page 1. Man, nude, standing up. 2. Female fully draped, walking. 3. The same figure, extending one hand. 4. Anubis in a short mantle. 5. The usual figure of the Abraxas god. 6. Bird-headed man surrounded with rays (Phre?). 7. Bust of Serapis. 8. Female reclining. 9. Terminal figure in the form of a cross. 10. Frog. 11. Ibis, or Phoenix. 12. Female holding above her head a star-spangled veil. Montfaucon supposes all these figures represent the genii who preside over the hours of the day–the first being expressive of rising, the last of night; and calls attention to the fact that the seventh page is assigned to Serapis, who sometimes receives the title of ἑπταγράμματος θεός. But in his Plate 188, Montfaucon copies from Bononi’s ‘Museum Kircherianum’ another leaden book “found in a sepulchre,” which actually has seven pages, and two figures heading each, in the specimen pages: and this may possibly be the one since published in its entirety by Matter; although at present the leaves are separate, not connected into a book, which may be the result of accident during the century and a half that has elapsed since it was first noticed.

-

Wolfgang Helbig, Emil Reisch, Führer durch die öffentlichen Sammlungen klassischer Altertümer in Rom, Band 2. Leipzig: Verlag von Karl Baedeker, 1891, p.372. English translation in: Wolfgang Helbig, Emil Reisch, Guide to the Public Collections of Classical Antiquities in Rome, trans. James F. and Findlay Muirhead, Vol. II. Leipsic, Karl Baedeker, 1896. p.415-416 & p.421. Second German edition with numbers assigned (no.1451) published 1899, p.411.

Leaden Book. Each cover of this book bears a bust in relief in the centre, the front cover a veiled woman, the back cover a bearded man. Within the covers were seven very thin leaden leaves, originally fastened by a hinge but now exhibited separately. They are inscribed on both sides with an unintelligible series of Greek, Latin, and Italic letters, while in the upper third of each page are scratched two human or animal figures, or two symbols. The source of this book is not quite clear. The style and the writing are both very remarkable, but the article is held to be genuine and is believed to be a mystical book of the Basilidian Gnostics. Comp. De Ruggiero, Catalogo, pp. 63-79, No. 199

-

Angela Mayer-Deutsch, Das Musaeum Kircherianum: Kontemplative Momente, historische Rekonstruktion, Bildrhetorik. Zurich: Diaphanes, 2010. p. 142.

Gleich nach dem Sistrum wird bei Bonanni ein eventuell gefälschtes Buch aus Blei (Taf. 4,08ab)42 beschrieben, das sich um 1899 unter Ruggiero noch im Museo Kircheriano befand.43

Immediately after the sistrum a possibly fake book of lead (Pl. 4,08ab)42 is described in Bonanni, which was still around in 1899, under Ruggiero in the Museo Kircheriano.43

Bibliography (Kircher & the Kircherian)

Collected here are some of the works I’ve consulted in my research which are about Kircher or the Kircherian museum, which contain no apparent reference to the object(s) at hand. See also Athanasius Kircher at Stanford and the more comprehensive bibliography and online works of Kircher published by Hole Rößler.44

- Alberto Bartola. Alle origini del Museo del Collegio Romano. Documenti e testimonianze. Nuncius 1, 2004. p. 297-356.

- Mordechai Feingold, ed. Jesuit science and the republic of letters. Cambridge, Ma.: MIT Press, 2003.

- Paula Findlen, ed. Athanasius Kircher: The Last Man Who Knew Everything. New York: Routledge, 2004.

- John Fletcher, ed. Athanasius Kircher und seine Beziehungen zum gelehrten Europa seiner Zeit. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1988.

- Rosanna Friggeri. The Epigraphic Collection of the Museo Nazionale Romano at the Baths of Diocletian. Milano: Electa, 2004.

- John Glassie. A Man of Misconceptions. The Life of an Eccentric in an Age of Change. New York, 2012.

- Joscelyn Godwin. Athanasius Kircher: A Renaissance man and the quest for lost knowledge. London: Thames and Hudson, 1979.

- Joscelyn Godwin. Athanasius Kircher’s Theatre of the World: The Life and Work of the Last Man to Search for Universal Knowledge. Rochester, Vt.: Inner Traditions, 2009.

- Nathalie Lallemand-Buyssens. Les acquisitions d’Athanasius Kircher au musée du Collège Romain à la lumière de documents inédit. Storia dell’arte 133, 2012. p. 107-129.

- Louis Moréri. Le grand dictionnaire historique. 1759. Vol. 6, p. 37.

- Eugenio Lo Sardo, ed. Athanasius Kircher: il museo del mondo. Rome: De Luca, 2001.

- Eugenio Lo Sardo, ed. Athanasius Kircher: il museo del mondo (guida breve). Rome: De Luca, 2001.

Bibliography (Bonanni)

Collected here are works I’ve found about Bonanni himself, a relatively obscure figure in comparison to Kircher.

- Filippo Buonanni, Rerum naturalium historia nempe quadrupedum insectorum piscium variorumque marinorum corporum fossilium plantarum exoticarum ac praesertim testaceorum exsistium in Museo Kircheriano. Rome: 1773. p.XXXVII.

- Giammaria Mazzuchelli, Gli scrittori d’Italia, cioè, Notizie storiche e critiche intorno alle vite e agli scritti dei letterati italiani. Brescia: Bossini, 1753-1763. Vol. II Parte IV p.2329-2333.

Footnotes

-

I would note here that I have copied the English translation from the placard, which for some reason, omits “basilidian,” and seemingly mistranslates “in probabile successione (“probably in sequence”) as “probably at a latter date” and “testo” (“text”) as “date”. ↩ ↩2

-

I make this assertion on the basis that Brunati observes it in the Kircherian in 1837 in his Musei Kircheriani, and Reisch describes observing the codex in the Kircherian as it remained in 1891. The Baths of Diocletian was instituted as the inaugural seat of the Museo Nazionale Romano in 1890, so the codex may have been moved between then and the Kircherian’s ultimate dissolution in 1913. ↩ ↩2

-